MILDRED VALLEY THORNTON

Canadian 1890-1967

Biography

AVAILABLE WORKS

SELECT SOLD

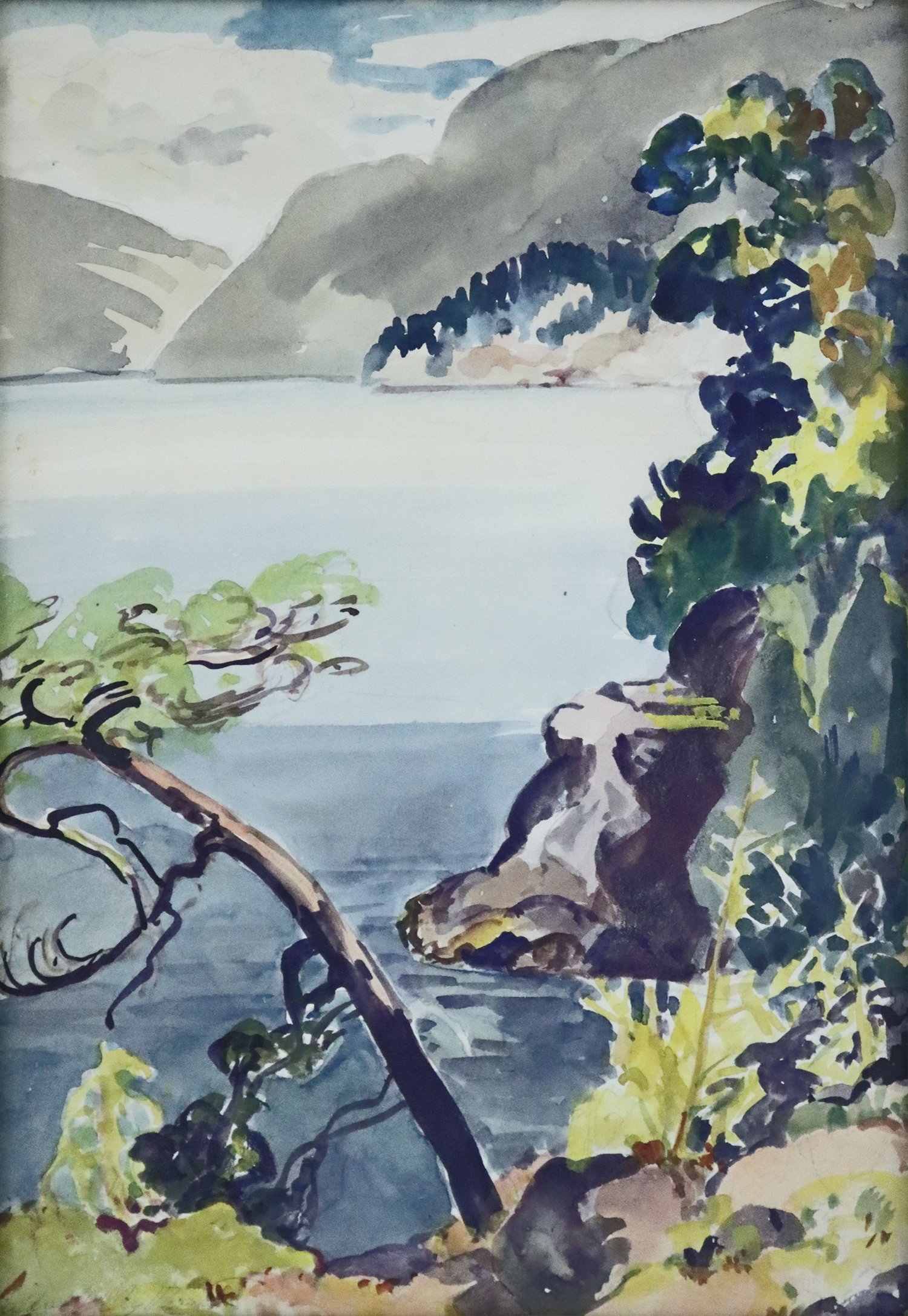

Famous for her portraits portraying the First Nations people of Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, Mildred Valley Thornton is also known for her landscapes, mythological and historical subjects in oil and watercolour. She had a lifelong passion for painting aboriginal people and events, attempting to recapture on canvas the vanishing culture of the indigenous communities. She travelled extensively and was a tireless advocate of Indigenous and women’s rights and arts communities.

Mildred Valley Stinson was born on a rural farm into a large family in Dresden, Ontario in 1890. Despite attending school in a one-room schoolhouse, she came from a cultured and educated family on her mother’s side. She likely developed an interest in art from her family as her maternal grandfather and two uncles were artists and her aunt Evelyn Beatric Longman an accomplished sculptor. Following family tradition in 1907 at the age of seventeen Mildred began her early training at Olivet College in Michigan, graduating in 1910 from a three-year program with an art supervisor’s certificate. She briefly attended the Ontario College of Art in Toronto where she studied under George Agnew Reid and John William Beatty. She befriended Beatty, and through him was influenced by Tom Thomson who became her favourite artist.

Seeking adventure, in 1913 Mildred travelled to Regina to stay with an uncle and subsequently remained in Saskatchewan where she gave private lessons and sold landscape and portrait studies. She fell in love with and in 1915 married the gentle businessman and restaurateur John Henry Thornton who was a steadfast supporter, both financially and emotionally, of her artistic career. In 1918 she attended the Art Institute of Chicago to further her training, while John stayed in Regina, and by 1920 she was teaching at the Regina College of Art where she became head of the art department. With the arrival of artists James Henderson and Augustus Kenderdine the Regina College School of Art became one of Canada’s prominent artistic scenes. At 36 Mildred became pregnant with twins, and in her first trimester travelled to Ontario to paint in Algonquin Park; the difficult journey was eased by her connection to where Tom Thomson painted and lost his life. The twins Jack and Maitland were born in 1926, and John continued to support Mildred as she travelled often for weeks at a time. She befriended fellow artist Reverend Duncan MacLean and the two travelled together, sharing a passion for advocacy and a love for painting the prairie landscape.

It was in Regina that an earlier interest in the Indigenous peoples from her childhood was rekindled, and in 1928 Mildred began to paint First Nations subjects in earnest. She would pay her sitters and had genuine curiosity and interest in her subjects, capturing them in situ and disregarding the studio setting popular at the time. During this period, she visited many of the Plains tribes including Cree, Blackfoot, and Sioux. She would often paint portraits but would at times also paint landscape views, or mythological or historical paintings from stories told to her in these communities. In some cases, the portraits she painted were the only recorded likeness of her sitters and during her lifetime none of these portraits were for sale.

As an active member of the Saskatchewan arts and culture community, Mildred became a member of many groups and associations including the Local Council of Women, the Regina Sketch Club, the Saskatchewan Women’s Art Association, the Poetry Group, and was a founding member of the Saskatchewan Painters’ Guild. She lectured and organized poetry readings and conferences, championing for local artistic talent. She held several exhibitions including over fifty paintings in the Canadian Pacific Railway Hotel Saskatchewan in 1930, and during this time painted the portraits of many distinguished and political figures. As one of Saskatchewan’s prominent artists, she was asked to organise a representation of Saskatchewan artists for the 1930 Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto, alongside BC artists such as Emily Carr, Frederick Varley and W.P. Weston. She actively exhibited with the Ontario Society of Artists, The Royal Canadian Academy and the Montreal Museum of Arts throughout this period.

By 1934 the Great Depression caused the Thornton family to move to Vancouver to seek new opportunities. After a brief time in a Vancouver boarding house Mildred left John in Vancouver and travelled to Toronto to stay with her friend, artist Alice Innes. The family was reunited in Vancouver 7 months later where John had opened a confectionery on West Broadway near Main Street and secured a house to rent. Mildred wasted no time in organising an exhibition at the Hudson’s Bay in 1935, followed by a solo exhibition at the Vancouver Art gallery in 1936 with 88 works. She exhibited at the B.C. Provincial Museum in 1942 and regularly in the Annual B.C. Artists and B.C. Society of Fine Arts exhibitions, often beside such artists such as B.C. Binning, Emily Carr, Lawren Harris, and W.P. Weston. As the family situation improved Mildred and John bought a house near English Bay, where Mildred set up her painting studio in the dining room.

Mildred continued to paint the First Nations community, focusing now on the West Coast including the Haida, Tsimshian, Nisga’a, Gitxsan, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Salish. Often visiting remote destinations difficult to access, she travelled extensively and used every means of transport available to her. Her paintings showed her respect and admiration for the First Nations, documenting community life including potlatch, rituals, whaling, and handiwork, along with her portraits. She documented their lifestyle, traditions and rituals, travelling and lecturing advocating to increase awareness for aboriginal rights. She continued to work portraying the B.C. outdoors and mountains, first sketching in watercolour and then reworking in a larger format in oil or watercolour in her studio. These vibrant works are loosely painted and express her love of the magnificent Canadian landscape. During this time she would sometimes base her works after photographs by her friend John Vanderpant, and travelled throughout the province with her friend and art dealer Reg Ashwell. Although Mildred Valley Thornton and Emily Carr painted similar subjects at the same time and were often compared, the two artists disliked each other and had little in common.

This was an extremely productive time for Mildred artistically, culturally and with social advocacy. Very active in the Vancouver arts community, she was affiliated with numerous organizations including the Vancouver Poetry Society, taught at the Commercial and Fine Arts Training Centre and organised many exhibitions. An executive member of the Community Arts Council, Mildred was part of the 1949 Design for Living exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery which was very well received. As a free-lance journalist she wrote for many publications and worked as an art critic at the Vancouver Sun from 1944 to 1969. She reviewed books, joined the Canadian Women’s Press Club, and contributed to The Native Voice, the first aboriginal newspaper founded by her friend Maisie Hurley.

Through the Totem-Land Society Mildred befriended artist Ellen Neel and the two developed a strong friendship. They had much in common, both passionate about advocating for women artists and preserving the traditional arts of the aboriginal people. Mildred frequented the Neel family Totem Art Studios shop in Stanley Park and became a supporter of Ellen’s work, purchasing many of her carvings. When Ellen died in 1967 Mildred wrote a touching tribute, and her portrait of Mungo Martin, Ellen Neel’s uncle, is held in the McMichael Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario.

After her husband’s death in 1958, Mildred moved to London, England to be closer to her son Maitland. During her time in England she continued to paint, was given a major exhibition at the Royal Commonwealth Institute and became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. She lectured at both the Royal Commonwealth Society and Commonwealth League. She returned to Vancouver in 1961, and in 1966 her book Indian Lives and Legends was published, an account of her experiences painting the First Nations of British Columbia. She died in Vancouver in 1967 at the age of 77.

During her life Thornton amassed a large collection of First Nations artifacts, either as gifts or purchased during her travels. When she moved to an apartment her collection was purchased by the B.C. Provincial Government, and her sound recordings of interviews and events by the B.C. Archives. She had actively sought to place her First Nations portraits in a public institution but without luck, so shortly before her death she added in her will that they should be sold as one lot at auction or burned. Fortunately, the codicil to the will had not been properly witnessed, and her paintings capturing the vanishing culture of the First Nations of Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia were saved. After her death her physician Dr. Laurie Patrick and his partner Uno Langmann handled the estate, then The Art Emporium and later Westbridge Fine Art, with Westbridge holding an exhibition and sale of ninety paintings in conjunction with Butler Galleries in 1985. Although the interest from institutions was minimal, her works were popular with private collectors. Today her work is collected both privately and by public institutions, including many band councils seeking their ancestors’ portraits.

Mildred Valley Thornton was a charter member of the Saskatchewan Women’s Art Association, President of the Canadian Women’s Press Club, a member of the Native Sisterhood of B.C., and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, England. Her paintings are in the collection of private and corporate collections in Canada, England and the US, as well as the National Gallery, the Glenbow Museum, the McMichael Collection, the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Royal B.C. Museum, and Simon Fraser Art Gallery. She was honoured by many First Nations tribes including the Kwakwaka’wakw who made her a princess of the Clan Eagle. The Kwakwaka’wakw titled her "Ah-ou-Mookht" meaning "she who wears the blanket because she is of noble birth", the Cree "Owas-ka-ta-esk-ean" meaning "putting your best ability for us Indians" and the Blackfoot “Mo-jai-sin-a-ki meaning “the one who makes us pictures”. In 1999 she posthumously became an Honourary Member of the Canadian Portrait Academy. Her second book Buffalo People: Portraits of a Vanishing Nation was published posthumously in 2000. In 2011 Sheryl Salloum published a comprehensive biography The Life and Art of Mildred Valley Thornton as part of The Unheralded Artists of B.C. series.